Carbon Contracts for Difference: The Netherlands

Over 150 countries, accounting for two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions, now have a net-zero target in place or under discussion.

Overview

Over 150 countries, accounting for two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions, now have a net-zero target in place or under discussion. But considerable policy support will be required to scale the deployment of low-carbon technologies needed to meet these goals. For the materials and industry (M&I) sectors, heavy material production, like steel and cement, will become reliant on new low-carbon technologies to decarbonize, but the uptake of new processes will depend on sufficient incentives on both the demand and supply side.

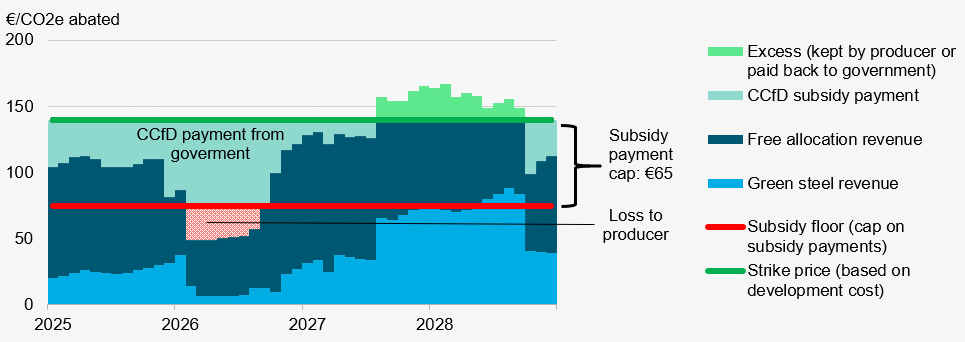

Contracts for Difference (CfDs) and Carbon Contracts for Difference (CCfDs) are being explored in several countries as policy instruments to support the adoption of low-carbon solutions. In a CfD, when the ‘strike price’ (the cost of production to achieve a return) of a low-carbon fuel exceeds the ‘reference price’ (typically based on the market price of status-quo production), the government compensates the producer for the revenue difference. This mechanism incentivizes producers to promote a low-carbon fuel or technology that is not yet competitive with fossil-fuel-based alternatives.

A CCfD works similarly and can be implemented on both the demand and supply side. In this case, the reference price is based on the sum of the carbon price, for example, under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), and market revenues. In a demand-side CCfD scheme, the government pays out the difference if the additional cost of the low-carbon technology is not covered by market revenues and the sale of emission allowances (carbon permits). In a two-way CCfD, the government’s risk is also protected: when the price of a low-carbon fuel, and therefore the revenue, exceeds the production costs, the producer pays back the surplus to the government. This policy mechanism both protects the government for taking this risk and rewards them if the technology becomes competitive with traditional fossil-fuel-based alternatives.

Source: European Commission, BloombergNEF. Note: Market prices and costs are estimated to illustrate the policy mechanism.

CCfDs provide a predictable revenue stream to industrial players making long-term decarbonization investments. They also reduce the burden on governments by only subsidizing the price difference between market revenues plus the of free allowances and what a company requires to turn a profit. CCfDs directly ensure the carbon neutrality of the new technology and in theory offer a cheaper subsidy to governments since they also rely on the sale of allowances. However, it can also be riskier and more challenging financially for governments to rely on a potentially volatile carbon price. The choice between CfDs and CCfDs depends on the maturity and stability of a country’s carbon price.

The Sustainable Energy Transition Scheme (SDE++) in the Netherlands is an example of a one-way supply-side CCfD scheme, meaning the producer does not have to pay the surplus back to the government. The government protects its risk by instead including a price floor, which caps the total top-up it will pay if the market price of the technology and carbon revenues fall below a certain level. The program offers producers an operational subsidy for renewable technologies in electricity, heat, gas and low-carbon heat, and low-carbon production technologies. Subsidy applicants are chosen based on the emissions intensity of their technology and are required to continue tracking and reporting their emissions via industrial net metering after receiving the subsidy.

Impact

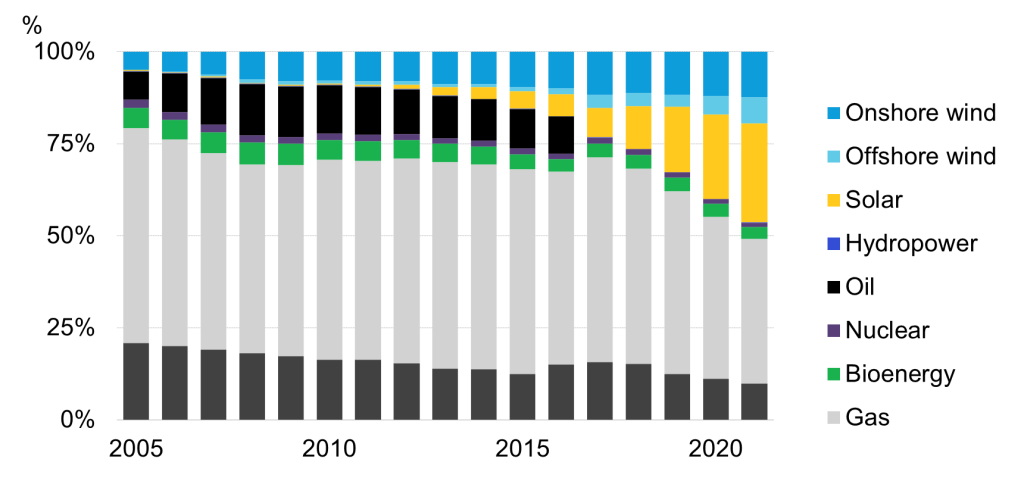

The SDE scheme began in 2008 and was particularly influential in incentivizing new solar installations. Since 2008, SDE broadened to SDE+ to include more technologies. SDE++, introduced in 2020, takes the program one step further by shifting the evaluation criteria from energy generated to carbon avoided. The SDE scheme has historically contributed most meaningfully to traditional renewables deployment, helping increase solar’s share of the installed capacity mix to 27% and wind’s share to 17%.

Source: BloombergNEF

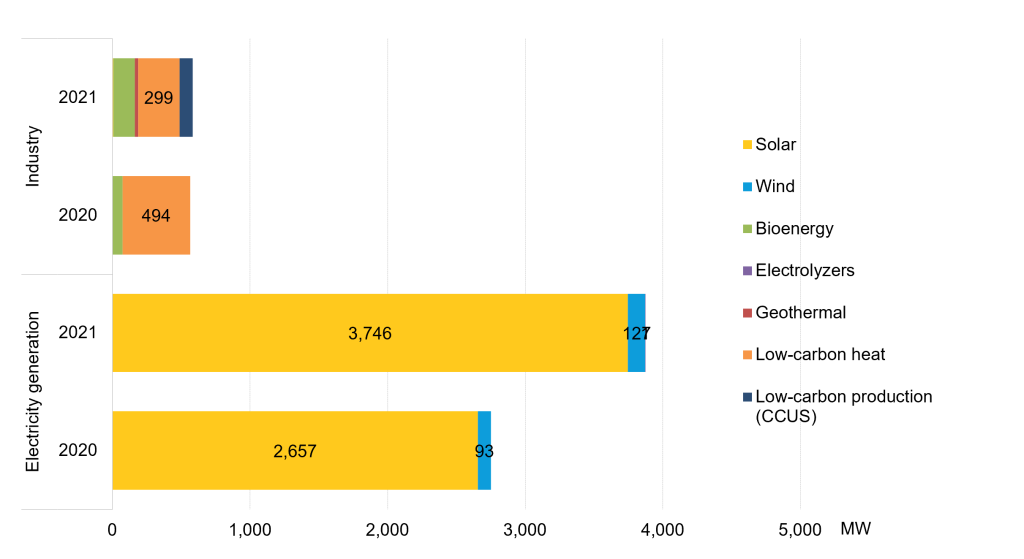

Source: The Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO), BloombergNEF. Note: “Industry” includes heat and co-generation.

Additionally, the Netherlands has phased out oil almost entirely and decreased reliance on gas from 58% of the grid’s capacity in 2005 to 39% in 2021. Since the expansion of the policy to SDE++, low-carbon heat and production technologies, such as carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), have begun to receive subsidies, accounting for 890 megawatts since 2020.

Opportunity

Following SDE++ as a successful model for CCfD, other governments, including policymakers in the UK and European Union, are exploring this mechanism to accelerate the deployment of clean hydrogen and other low-carbon technologies. On May 18, the European Commission released its plan to implement REPowerEU – the bloc’s strategy to phase out the use of Russian gas and cut European gas consumption by more than half by 2030. The plan relies on diversifying gas supply, as well as leaning more on wind, solar, energy efficiency and clean hydrogen to achieve these goals. CfDs and CCfDs could reduce the outlay for government and taxpayers and increase revenue certainty for project owners. The EU plans to use both methods to target the demand and supply side by focusing on the natural gas phase-out for producers and transitioning to hydrogen-based processes for industrial end users.

Source

BloombergNEF, The Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO), European Commission

Learn more about BloombergNEF solutions or find out how to become a BloombergNEF client.