Electric Vehicle Charging Incentives

Speed deployment of EVs & charging infrastructure for road transport

Overview

The availability of charging infrastructure could pose a significant barrier to the roll-out of electric vehicles (EVs) – a crucial element of any government’s net-zero strategy. Yet, for some markets, the EV fleet remains small, increasing the risk that public charging stations would be underutilized and their economics challenging. Securing financing on reasonable terms may also be a barrier due to uncertain future demand for charging. As a result, government support is needed, both to promote home and workplace installations, as well as build-out of public charging stations.

Source: BloombergNEF

Impact

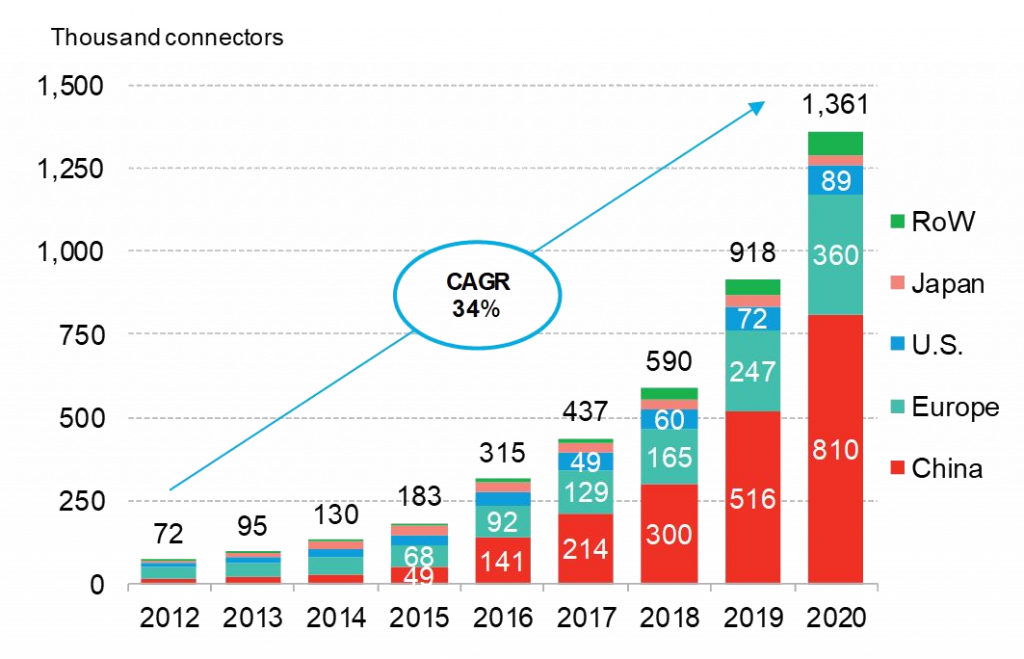

Some governments are providing significant financial and regulatory support for charging infrastructure deployment. This has helped to reach 1.4 million public charging connectors installed by end-2020 – a rise of 48% on the preceding year.

China accounted for two-thirds of global installations in 2020, with some 111,000 in December alone. This is more than the entire size of the network in every other country. Its dominance is partly driven a lack of home and workplace charging options, while in Europe and the U.S., for example, private infrastructure is more common.

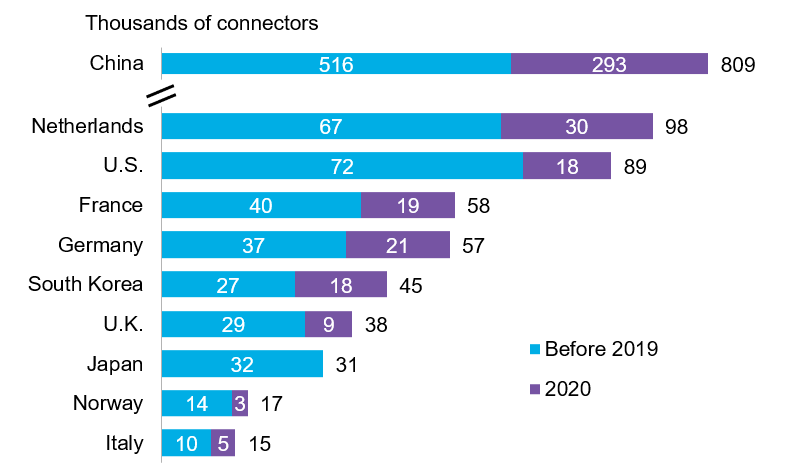

These installations mean that worldwide, there were some 7.4 EVs per public connector at end-2020. However, this ratio varies significantly across countries, with 5.4 EVs in China, 3 in Netherlands and 25 in Norway.

Opportunity

Reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 means significantly more EVs and thus infrastructure are required: 60% more chargers are built globally by 2050 under a net-zero scenario compared with a world where current techno-economic trends continue and no new policy is implemented, according to BNEF’s Electric Vehicle Outlook 2021. This also significantly increases the need for government support at all levels – national, state-level and municipal.

Policy makers have a range of types of incentive at their disposal to ensure the required charging infrastructure is built. A number of governments have announced deployment targets: the U.S. and France aim to reach 500,000 and 7 million public chargers by 2030. Both goals will be a challenge to meet, from their 2020 installation total of 89,175 for the U.S. and 39,600 for France. It is unclear what happens if these targets are missed, but they signal a government’s intended direction.

Instead of quantitative goals, some policy makers plan to install chargers at specific locations on the road transport network, for example. South Korea intends to build high-voltage quick chargers at all expressway service stations, while Costa Rica plans to have one charging station every 80 kilometers on national roads.

Governments at all levels can help promote infrastructure roll-out by offering financial and fiscal incentives to owners of residential or commercial buildings. For example, the Canadian government announced at end-2020 that it would invest a further C$150 million ($119 million) over three years in charging stations. The U.K. offers grants to individuals for charging-point installation, while in the Netherlands, businesses can apply for the Environmental Investment Allowance – an investment deduction of up to 36% of the amount invested into a charging point. Tax credits are available in the U.S. states of New York, Washington and Louisiana, for example.

Some countries also included support for EV charging infrastructure in their Covid-19 recovery plans, including Germany, the U.S. and the U.K. These funds are to be distributed in a range of ways to support charging at homes, workplaces and in public. Enabling grid connections for charging at key locations is a focus area for funds like the U.K’s $698 million rapid charger fund.

Source: BloombergNEF

Regulation can also play an important role in ensuring infrastructure build-out: in the Netherlands, in urban areas, every EV driver has a right to a charging station within 200 meters of their home. This has helped the country install the most public connectors in Europe, with 97,500 by end-2020. The EU in general is seeking to promote charging through building regulations: for example, new large non-residential developments or existing buildings undergoing major renovations must have at least one charging point and enough “ducting infrastructure” (ie, electric cabling) to enable installation of charging points for at least one in every five parking spaces.

Other policy makers have implemented similar mandates: the U.S. city of Chicago, for example, requires residential developments of 24 units or more to provide at least two EV-ready parking spaces (ie, the developers must lay the foundations but don’t have to install the chargers), and in the Australian Capital Territory, all multi-tenanted properties and mixed-use developments must include charging.

Some policy makers have also taken an active role in promoting interoperability, open standards and smart charging. For example, Europe’s EV charging infrastructure network is fragmented. Due to the lack of standards in the early days of the market, EV drivers need a variety of memberships, accounts, cards and apps in order to access various public charging points. The situation is improving. At the EU level, all new public EV charging point must comply with Type 2 chargers (for AC charging) and Combo 2 chargers (for DC charging). Moreover, member states have to ensure that charging points are usable by any EV driver without pre-registration regardless of their home country. The EU has also sought to promote open standards through public-private partnerships such as Green eMotion and PlanGridEV.

Source

BloombergNEF. Extracted from How European Policymakers are Approaching EV Charging report, published on February 25, 2019. Learn more about BloombergNEF solutions or find out how to become a BloombergNEF client.

Read next

Related actions

Speed deployment of charging infrastructure for passenger vehicles and trucks

- Transport

- Financials

- Consumers

- Companies