Public Finance and Support for Just Transition

Leverage public funds to support a just transition of communities

- Asia

- Central & South America

- Europe

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America & Caribbean

- Oceania

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Power and Grids

- Industry and Materials

- Transport

- Buildings

- Agriculture

- Financials

- Companies

- Consumers

- International

- National

- Regional

- 3. Phase out carbon-intensive activities

- 4. Create appropriate climate transition governance

Overview

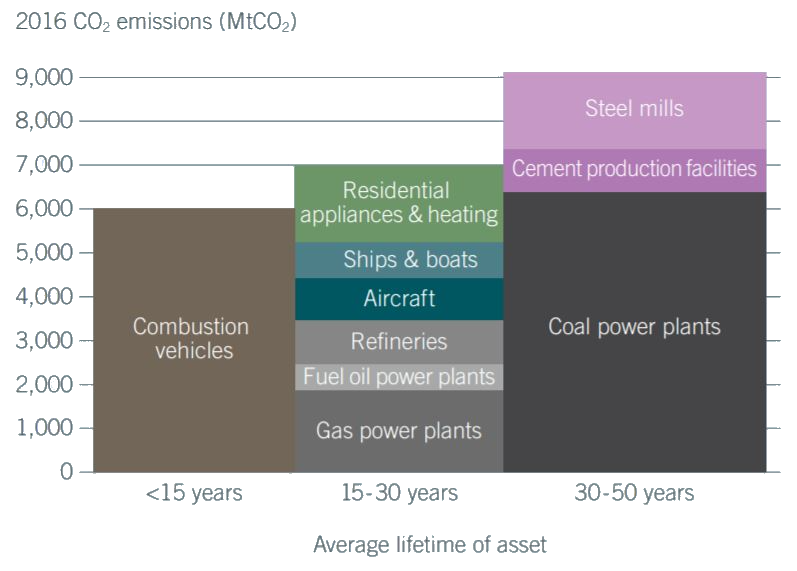

Many assets in the real economy are long-lived, ranging from around 15 years for cars and buses to 50 years for fossil-fuel power plants to 100 years or more for buildings. As a result, the financing and investment decisions of the past can lock in carbon emissions well into the future. “Committed” emissions from existing fossil fuel–based assets in the power, industrial, and transport sectors are already incompatible with a 1.5-degree trajectory.

The transition to a low-carbon economy will need to address the fate of these existing carbon-intensive industries and assets. The importance of engineering a just transition for workers and affected communities is now broadly understood. Curtailing the economic lifetimes of power plants, factories, and vehicles also poses the possibility of financial losses for those who invested equity or debt on the assumption of long-term operating revenues. More broadly, the corporations that manufacture, own, and operate these assets often have long-standing business models reliant on carbon-intensive industries and equipment.

The financial sector can play an important role in facilitating the transformation of carbon-intensive sectors by offering financing solutions to businesses as they undertake the low-carbon transition. The public sector can facilitate an orderly transition by supporting affected communities and by creating clear policy frameworks to allow the private sector to plan for the phase-out of the most carbon-intensive assets.

The long lifetime of assets in the real economy — such as power plants, steel mills, vehicles, and buildings — and the emission intensity of those assets together contribute to carbon lock-in. Carbon lock-in is also promoted by the desire to preserve jobs associated with sectors like coal mining and fossil-fuel transport. These broader societal and economic factors can drive political opposition to the phase-out of emission-intensive assets and the introduction of more cost-effective, low-carbon alternatives.

Source: Rocky Mountain Institute

Impact

Breaking carbon lock-in will require some emission-intensive assets to be retired early while transforming the corporations, utilities and enterprises whose business models are based on the operation of such assets. However, as early retirement reduces the returns anticipated at the time of initial investment and creates additional costs of decommissioning, meaning losses in financial value could follow.

The challenge of managing early retirement is already a reality for coal-fired power plants, which are among the longest-lived and most carbon-intensive assets. In places such as the U.S. and Europe, economic forces are leading to reductions in coal-fired power generation — many of which are older, less efficient facilities — due to lower natural gas and renewable energy costs, and the advent of battery storage. U.S. power providers shuttered coal plants at a record rate in 2018; electricity generated from coal fell by 36% between 2008 and 2017. Coal use for energy in the EU also fell by 36% over the same period.

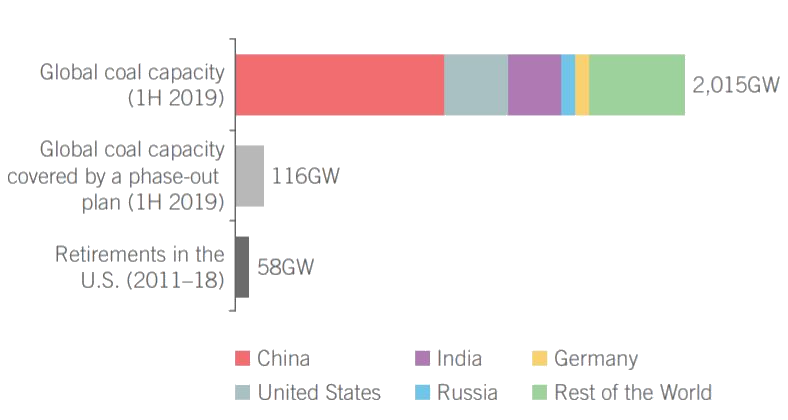

The market-driven reduction in coal generation alone is unlikely to achieve the pace of phase-out needed. Unabated coal-fired power generation (ie, generation without carbon capture and storage) would need to be phased out entirely by 2050 to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement and require the retirement of about 1,200GW of existing coal-fired capacity before the end of its economic lifetime. A large share of these retirements would be in high-income and newly industrialized countries — particularly China, which operates the largest number of coal-fired power plants today. To speed up the coal transition, some nations have implemented coal phase-out policies, which can help create certainty for corporations and investors to proactively plan for the transition away from coal. However, such policies have been introduced only for a small share of the existing global coal fleet.

Where phase-out plans exist, they usually encompass a range of elements, including regulatory action and support for a just transition for workers. For example, Germany’s recent commitment to phase out coal power by 2038 is supported by a clear decommissioning roadmap, compensation payments to households that may face higher energy bills as a result of the phase-out, and 40 billion euros in public resources to invest in the regions most affected by the policy.

Changes to public utility regulatory frameworks can also incentivize the early retirement of coal plants owned by generators that sell electricity at regulated prices. For example, regulated utilities can use rate-reduction bonds to refinance remaining debt on coal-fired power plants. The utilities can issue low-interest rate bonds backed by securitized future cash flows from ratepayers to finance the decommissioning of coal assets. This approach, known as coal securitization, is gaining momentum in the U.S. in areas with a large legacy coal industry such as Colorado and Michigan.

Transforming utilities in highly regulated environments, for example where a single public organization has a monopoly in the power sector, often requires targets to be paired with adjustments to regulated tariffs or budget transfers to finance new investments. Selling ratepayer-backed bonds to investors can allow utilities to recover the value of their investment, while retiring certain assets and reducing the potential cost to ratepayers.

Source: BloombergNEF, Coalswarm.

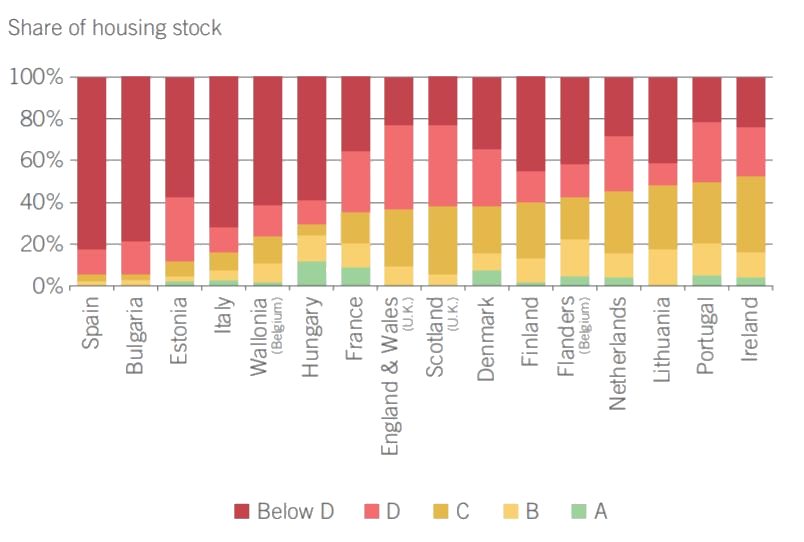

Buildings are among the longest-lived assets in the real economy, and their energy consumption for heating cooling, and electricity are significant sources of emissions. While decarbonizing the electricity supply can help reduce some of these emissions, many heating systems directly burn fossil fuels such as natural gas, fuel oil and propane. In addition, while efficiency standards for new buildings are now common, older units are often not subject to such regulations. In Europe, 80% of the buildings that will exist in 2050 already exist today, many of which have low energy-efficiency ratings.

Deep building retrofits that combine the electrification of energy end-use with efficiency improvements can help reduce emissions from the existing building stock. Zero-carbon heating is both feasible and commercially available through electrically powered heat pumps. However, the practice of retrofitting old buildings with heat pumps is relatively uncommon due to high upfront costs, including the need to improve insulation to make heat pumps work efficiently. Further, such energy-efficiency investments may be challenging for rented properties, as the benefits from savings in energy bills accrue to tenants, who may not own the building itself or be responsible for the heating system.

Governments have begun to roll out policies to incentivize retrofits, such as low- or zero-interest loan programs for retrofit investments and efficiency mandates for existing buildings. For example, New York City passed legislation requiring landlords to retrofit buildings with new energy-efficient windows, heating and cooling systems, and insulation beginning in 2024.

Private finance institutions have also begun to realize opportunities in building retrofits. Research has shown that mortgages on more efficient homes have lower default rates, and the market value of efficient homes often increases at higher than average rates. Around 90 banks, industry associations, research centers, and other stakeholders from across Europe support the work of the Energy Efficient Mortgages Initiative, which promotes the use of low- or zero-interest loans to homeowners for energy-efficient building renovations.

Source: Building Performance Institute of Europe. Note: This figure shows energy efficiency ratings according to Energy Performing Certificate (EPC) class. The EPC label is an EU-wide standard that captures the energy efficiency of a home with regards to both heating and electricity consumption. EPC ratings are on a scale from A to G, with A being the most efficient. Calculation methods may vary among countries.

Moving from individual assets to the corporate level, businesses that have been traditionally invested in emission-intensive industries are starting to transition their activities in anticipation of a low-carbon future. Many electric utilities have already invested in a low-carbon transition, and several oil and gas companies have also begun to diversify. For example, clean energy projects and assets accounted for around 90% of Enel’s 8.5-billion-euro capital expenditure and 16.2-billion-euro earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization in 2018, which saw a 3.8% rise compared with the prior year. In the oil and gas industry, Royal Dutch Shell expects to invest $1-2 billion per year in its “new energy solutions,” which include natural gas, wind, solar, hydrogen, biofuels, and nature-based solutions, and recently declared an ambition to double this to $4 billion per year. The French multinational oil and gas company, Total, plans to increase investment in low-carbon technologies from around 3% of total capital expenditure to 20% of its asset base over the next 20 years.

Opportunity

Building on the success of green and sustainable investments to date, investors and lenders can help by developing a wider range of financing to support companies that have adopted ambitious transition goals. Ultimately, this will create a virtuous cycle with more money invested in clean companies, which creates more appetite for this transition — lowering financing costs and ultimately leading to more investment. Corporations and investors can also support the just transition of communities and workers by incorporating social criteria into their investment decisions, investing in retraining programs, and recognizing the long-term value of inclusive growth.

Early retirement of assets such as relatively new coal-fired power plants will inevitably lead to some loss of financial value — this prospect drives the political economy of opposition to climate policy. At the corporate level, fundamental changes may be required for those whose business models are built on fossil fuels. Such transformation is inherently challenging, and corporations will need to develop in-house expertise and institutional agility to successfully transition in competitive markets.

In the near term, public budgets can provide direct support to households and workers affected by the transition while also investing in longer-term industrial strategies and retraining programs. However, public finance is inherently limited, and opinions vary as to whether and how taxpayer funds should be used to fund redistribution mechanisms and compensation for industrial transitions.

Government policy can create the enabling frameworks and incentives for owners and operators of carbon-intensive assets to engineer a transition away from high-carbon assets. This can be done through regulating the closure of carbon-intensive assets and legislation or the introduction of standards applied to existing assets. Such measures can be designed to offer a path for investors to decommission or retrofit carbon-intensive assets and avoid uncertainty for owners and operators as facilities are retired. One key challenge, however, will be political opposition from owners of carbon-intensive assets and affected communities.

Source

BloombergNEF. Extracted from DFLI report, published on September, 2019. Learn more about BloombergNEF solutions or find out how to become a BloombergNEF client.

Read next

Related actions

Manage the impact of the transition on jobs and businesses and train workers for a lower-carbon economy

- Power and Grids

- Industry and Materials

- Transport

- Buildings

- Agriculture

- Consumers

- Companies

- Financials

Phase out unabated coal-powered industrial facilities

- Industry and Materials

- Companies

- Financials

Embed just-transition considerations into policymaking

- Power and Grids

- Industry and Materials

- Transport

- Buildings

- Agriculture

- Consumers