Tax Incentives for Renewable Energy: United States

Ensure project bankability by mitigating offtaker risk and ensuring diverse and certain revenues streams

Overview

Tax incentives have been available in a number of countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, India, Indonesia and South Africa to improve the cost competitiveness and build of renewables and energy storage technologies. They are often one of the first policies implemented by a market new to clean energy, with renewables equipment (eg, solar panels) or assets eligible for exemptions or reductions on import duties or VAT, or for accelerated depreciation.

In the case of the U.S., where these incentives have played the most pivotal role, they take the form of tax credits. Broadly speaking, developers of clean power projects can use the production tax credit (PTC) (primarily to support onshore wind) or the investment tax credit (ITC) (primarily for solar, but now also offshore wind).

The PTC gives tax credits pegged directly to production – for each megawatt-hour of electricity a qualifying project generates, the owner receives a credit that can be applied directly to its tax bill. The credit applies to the first 10 years of the project’s life. The ITC, which is also a credit a project owner can apply directly toward its tax bill, is equal to a percentage of the project’s qualified capital expenditure rather than being linked to production.

Impact

Despite its complexity, the tax equity system in the U.S. has underpinned renewables growth, with 108GW of wind and 73GW of solar installed by end-2020. On the downside, its tax equity system is more complex than other renewable-promoting policies elsewhere. It usually involves multiple parties (developers, sponsors, investors, and lenders), switches of ownership midway through project lifetimes, legal arrangements to facilitate these instances of shared or swapped ownership, and a sophisticated understanding of the tax code.

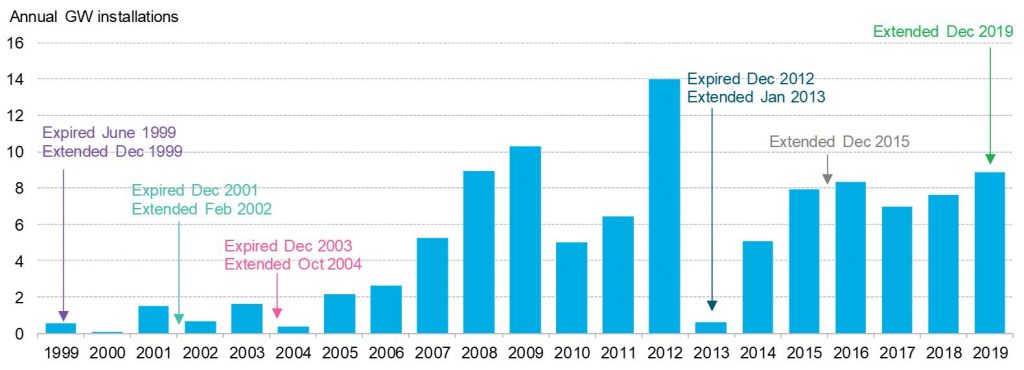

The PTC in particular has overcome many existential threats, relying on Congress to repeatedly extend it 2-3 years beyond its expiration date. Between 1999 and 2011, the PTC was allowed to lapse by Congress on three occasions without being immediately extended. Each lapse resulted in a precipitous drop in new installations, and these are visible in U.S. wind build in 1999-2005. An 11th-hour extension of the PTC in 2012 occurred too late to prevent a collapse of build in 2013. More recent extensions have not resulted in such abrupt drop-offs.

Outside the U.S., tax incentives have played a relatively modest role in renewables deployment. In early-stage renewables markets, they are most often implemented as a first-step incentive (potentially after the announcement of deployment target). Generally, tax breaks do not require significant financial outlay for the government and are simple to introduce. They are the most common policy type implemented in Sub-Saharan Africa, for example. But they also tend to make little difference to the project cost and thus have relatively little effect in terms of driving uptake compared with other policy types like feed-in tariffs and auctions.

* Source: BloombergNEF

* Source: BloombergNEF

Opportunity

The U.S. federal tax credits for solar and wind were extended and enhanced in a bill enacted in December 2020, together with new incentives for energy efficiency and carbon capture and storage. The extension to the offshore wind credit would cost $362 million, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. But BNEF’s preliminary estimate is much higher, at $14-22 billion.

However, the tax equity system has its downside: it exposes the renewables sector to the performance of the broader economy, specifically the profitability of long-term project investors, also known as tax-equity providers. When their profits are lower, these investors have less appetite for credits to offset their (lower) tax bill. This creates a supply crunch in years when demand for renewables is high but the economy is weak, as tax equity shortages can slow growth. Even if the number of tax-paying entities is sufficient to support sector growth in theory, relatively few have experience with this essentially complicated mechanism. This limits the pool of available investors (and therefore available tax equity dollars) to banks, utilities and a relatively small number of others, raising the costs of obtaining tax equity and therefore renewables.

This became abruptly apparent when the 2008 global financial crisis took hold. As credit suddenly froze, financial institutions posted enormous losses, eliminating their need for tax credits. The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) addressed this with the ’1603’ clean energy grant program, which allowed project owners to receive cash from the Treasury Department in lieu of the PTC or ITC. Similarly, the Covid-19 pandemic has created a tighter tax equity market, only available to trusted player shaving projects secured by long-term offtake contracts and willing to pay a premium interest rate.

Batteries are entitled to the full ITC only if they are charged using renewable sources, ie, requiring them to be charged from co-located renewable projects during their first five years of operation. This stunts their potential returns in the wholesale power markets and encourages developers to overbuild energy storage projects co-located with solar.

Because it is determined by the quantity of power generated, the PTC favors projects with higher capacity factors. Without it, onshore wind installations would likely become more geographically diverse. With a PTC no longer available, developers would prioritize locations where their projects could realize higher wholesale market prices – such as locations closer to load centers with less congested transmission systems.

Source

BloombergNEF. Extracted from G20 Policy Scoreboard report published on February 1, 2021. Learn more about BloombergNEF solutions or find out how to become a BloombergNEF client.

Read next

Related actions

Ensure project bankability by mitigating offtaker risk and ensuring diverse and certain revenues streams

- Power and Grids

- Financials

- Companies