Low-Carbon Hydrogen Policies: European Union

Support the deployment of low-carbon hydrogen

Overview

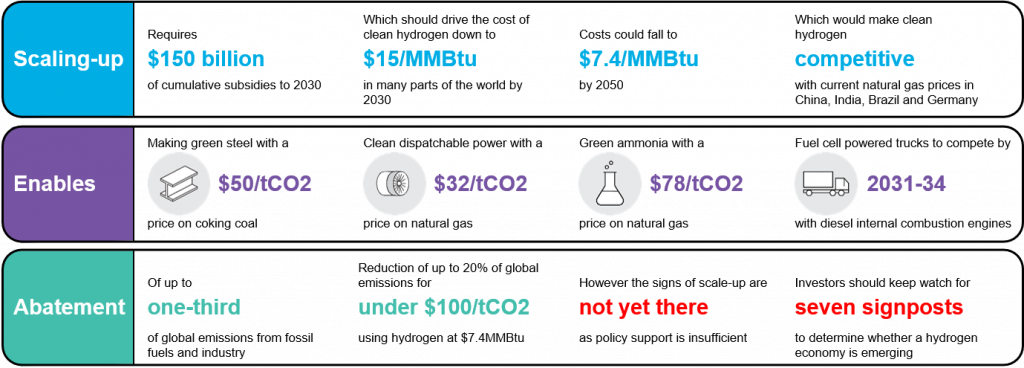

Hydrogen has the potential to play a critical role decarbonization across the global economy. Not only may it be produced with low or no greenhouse-gas emissions, it may be used for heating and feedstock in a range of applications, it can be transported and stored, and could also help to extend the useful life of existing gas infrastructure. Hydrogen could meet up to a quarter of the world’s energy needs by 2050, according to BNEF’s Hydrogen Economy Outlook. However, for this potential to be realized, the cost of hydrogen production must drop, demand needs to be created to help that cost decline and infrastructure must be built. All of this will require substantial policy support.

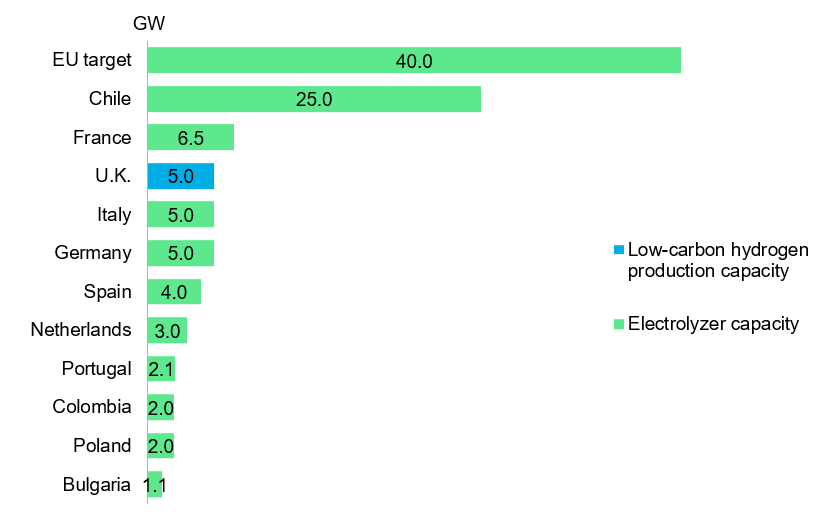

Today, nearly half of hydrogen produced is as an industrial by-product, while most of the remainder is made deliberately through fossil-fuel-based reactions. In 2018, less than 1% came from water electrolysis. If powered by renewables, electrolysis can produce zero-carbon hydrogen, while a low-carbon alternative is to use steam methane reforming or coal gasification with carbon capture and storage (CCS). On the demand side, almost all hydrogen is used as feedstock for manufacturing chemicals and basic materials. The volume produced via water electrolysis has mostly supplied small, distributed applications and its use is generally motivated more by economics, than a move to reduce emissions. However, governments are beginning to make pledges for electrolyzer installations, with varying degrees of ambition.

Source: Governments, BloombergNEF. Note: The Netherlands’ target is lower end of target range and Colombia’s is the mean.

Impact

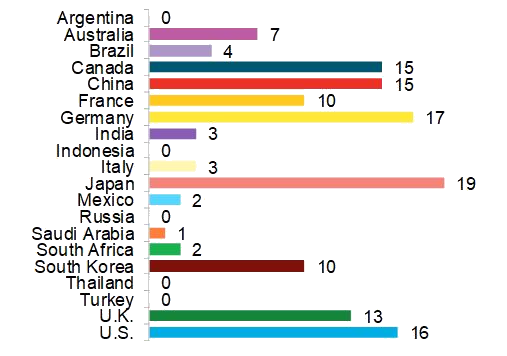

On paper, it seems there is no lack of government support for hydrogen consumption and production: such initiatives (including fuel cells) are incentivized by nearly 200 national-level incentives in the G-20 countries. In addition, a number of state or provincial governments have announced policies. However, many of these programs are not targeted specifically at hydrogen – rather they incentivize a wide range of low-carbon technologies. Examples are R&D funding schemes (such as Canada’s Low Carbon Economy Fund); renewable portfolio or fuel standards (eg, the U.S., South Korea); and carbon-pricing mechanisms which seek to promote the introduction of all low-emission technologies. In addition, many of them are only available to fuel cell vehicles – rather than promoting the use of hydrogen throughout the economy.

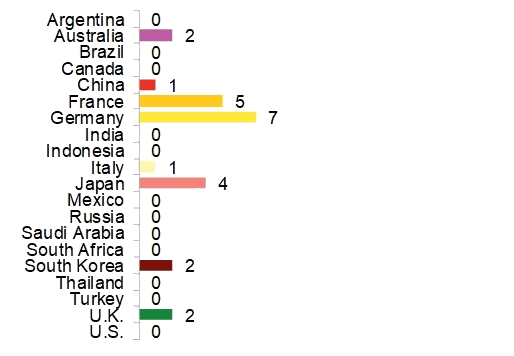

Removing the policies available to multiple technologies or only fuel cell vehicles reduces the total by 81%, with many of the G-20 countries having no dedicated support. This is problematic because hydrogen is not like other clean energy technologies such as PV or wind power or even other types of green gas like biogas or biomethane – both in terms of cost and potential role in the energy system. For hydrogen to reach its potential or to create a ‘hydrogen economy’, dedicated policies are needed to scale up production and consumption in a range of sectors in a commercial setting and bring down technology costs, and ensure the right infrastructure is in place.

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: Includes national government policies that are in force.

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: Includes national government policies that are in force.

Opportunity

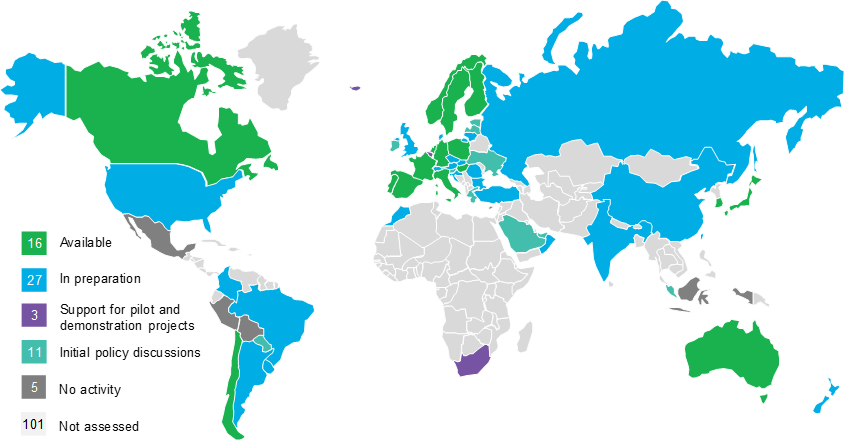

In terms of specific policies, the most common type to date is a hydrogen strategy or plan: as of August 2021, 16 countries have released a hydrogen roadmap, including Canada, France and Australia. Another 27 are under development – eg, Russia, Brazil and the U.S. Not all roadmaps are equal, however – they come with varying levels of funding and focus on different production methods and applications. Even if they do not have a roadmap, many governments offer direct subsidies to support the development of low-carbon hydrogen projects, with over $11.4 billion per year in national government support available, according to BNEF analysis. A further $4.6 billion per year in technology-neutral funding are to be available in the EU, from projects such as Horizon Europe.

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: As of mid-July 2021.

In addition to producing long-term strategy documents, some governments have agreed to pool resources and information to build know-how. Several have formed partnerships bringing together industry, other policy makers, non-governmental organizations, the research community and investors. The EU created the European Clean Hydrogen Alliance when it released its strategy in July 2020. Other examples can be found in France (various ‘Commitments for Green Growth’), Italy (‘Hydrogen Table’), and the alliance between Germany and Morocco.

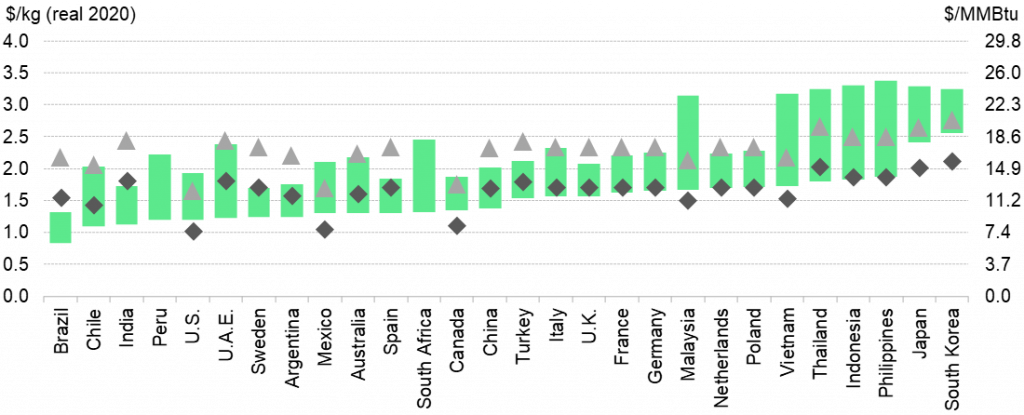

Governments wishing to build local hydrogen production capacity – whether for domestic consumption or export – need to introduce dedicated policies to promote demonstration projects of increasing size. This is the first phase of the scale-up and creation of a hydrogen economy, according to BNEF’s Hydrogen Economy Outlook. The overall goal of this phase is to scale up global low-carbon hydrogen production to some 2.7 million metric tons (MMT) a year in order to reach a delivered price of $2/kg by 2030. This will be a substantial increase from the 2018 total for deliberate production using renewables of less than 0.1MMT. We estimate that reaching this goal would require some 27GW of electrolyzers.

Source: BloombergNEF.

The EU and its member states stand out from the crowd in terms of hydrogen ambition: the bloc’s strategy includes a target to reach 40GW electrolyzer capacity by 2030. If achieved, this would lower the cost of producing renewable hydrogen in Europe by 60% to $1.5/kg within a decade, in line with our optimistic cost reduction scenario. Some EU member states have already stepped up to make ambitious pledges, notably Germany (5GW by 2030) and France (6.5GW by 2030). Outside Europe, Chile hopes to install 25GW by 2030. Australia’s federal government also avoided making a commitment in its long-awaited Technology Investment Roadmap released in September 2020. Instead it identifies economic tipping points where low-carbon technologies can start to compete with incumbent systems: specifically A$2/kg ($1.44/kg) for hydrogen produced from renewables or low-emission energy. The relevance and ambition of these thresholds are not clear as the Roadmap does not set a target deadline.

To achieve these strategies and targets, governments should implement dedicated fiscal and financial incentives such as grants and low-interest loans, to promote pilot and demonstration projects by cutting capital costs and risk. In addition, these programs need funding. Australia’s Technology Investment Roadmap falls down on both counts: it lacks policies to spur the necessary cost reductions and seems to rely on international investment and experience. In addition, at an event to launch the report, the government pledged some A$18 billion ($13 billion) of investment, but the vast majority comprises existing or previously announced funding. In contrast, Germany’s latest hydrogen strategy, which was released in June 2020, is fully funded, outlining the financing mechanisms, targets and instruments needed to kickstart the market. A total of 9 billion euros ($11 billion) has been allocated to funding hydrogen infrastructure both domestically and abroad: even though Germany aims to build domestic hydrogen production capacity this decade, it intends to rely on imports in the long term.

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: Assumes our optimistic electrolyzer cost scenario. Renewable LCOH2 range reflects a diversity of electrolyzer type, Chinese alkaline (low) to PEM (high). The electricity powering the electrolyzer is either PV or onshore wind, whichever is cheaper. Assumes equal CCS costs in all countries.

Producing renewable hydrogen will require substantial additional generating capacity, which will also need to expand due to the anticipated widespread electrification of end-use sectors such as transport and building heat. Under its hydrogen strategy, the EU aims to produce “up to” 10MMT per year of renewable hydrogen. We estimate that this would require some 195GW of new wind and solar plants – 120% the volume added by the EU-28 over 2014-19. On the bright side, expansion of electrolyzer capacity could create new revenue opportunities for wind and solar plants otherwise facing weakening investment signals due to low wholesale power prices. There is also an opportunity to produce some hydrogen from renewables curtailment.

So far, most of the limited financial support governments have offered to promote low-carbon hydrogen has come in the form of grants and concessional loan programs for early-stage technologies. As the hydrogen market scales, we expect these to be replaced with financial incentives for more mature technologies. These may be based on production or revenue, rather than investment, or be allocated through competitive processes. The EU and Germany are considering contracts for difference (CfDs), which would award companies a top-up payment equivalent to the price difference between the cost of carbon avoidance technology (eg, hydrogen) and the European carbon price. France’s hydrogen strategies also mentions industrial CfDs, suggesting growing interest in these policy mechanisms.

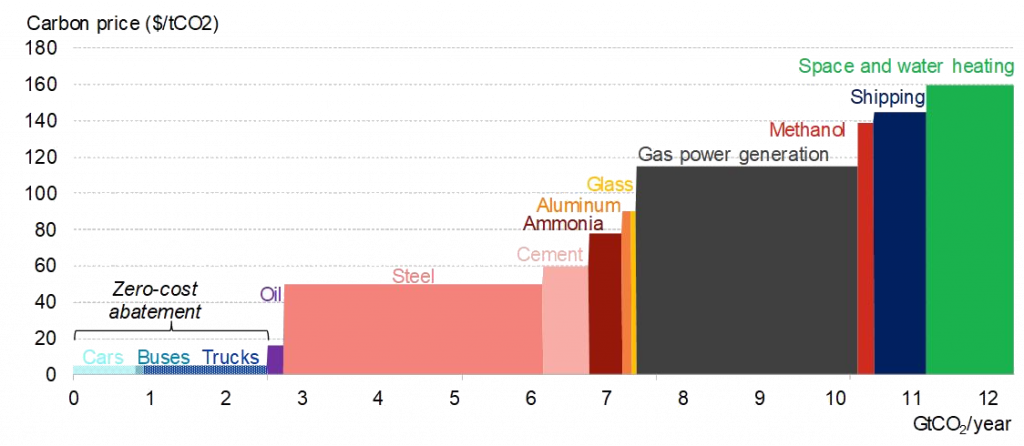

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: Sectoral emissions based on 2018 figures, abatement costs for renewable hydrogen delivered at $1/kg to large users, $4/kg to road vehicles. Aluminum emissions for alumina production and aluminum recycling only. Cement emissions for process heat only. Refinery emissions from hydrogen production only. Road transport and heating demand emissions are for the segment that is unlikely to be met by electrification only, assumed to be 50% of space and water heating, 25% of light-duty vehicles, 50% of medium-duty trucks, 30% of buses and 75% of heavy-duty trucks.

A true hydrogen economy will also require massive investment to adapt and install new transport and storage infrastructure. Policy has a role to play both in ensuring there is sufficient capital available and that the funds are disbursed optimally. Some countries have hydrogen infrastructure polices in place with the vast majority of these related refueling stations for fuel cell vehicles. Japan, China and France have deployment targets, while Canada, the U.K. and Germany as well as some U.S. states also offer financial incentives.

Governments need to ratchet up support to mitigate risk and reduce costs if they want the passenger road transport sector to make expansive use of hydrogen. Roadmaps and targets can help to show intent but they should be backed up by financial and fiscal incentives. These can seek to reduce the costs of infrastructure and/or improve its utilization (eg, by incentivizing the use of hydrogen and construction of electrolyzers). Given that such projects have long timeframes, government should focus on ensuring policy stability and transparency.

In light of the early state of deployment, countries with green hydrogen plans should note in their strategy documents that further policy work will be required in this area. For their part, the German government and the EU are already considering the regulatory changes required and coordinating changes across the electricity and gas networks. Going forward, a growing share of hydrogen will be manufactured away from the point of consumption and transported. In the early stages, it may be blended with methane at low levels in the existing gas distribution grid, requiring relatively minor upgrades to networks and some older appliances. This approach would defer some of the cost of switching to hydrogen and extend the useful life of existing natural gas infrastructure. In the longer term, alternatives will be required. High-capacity pipelines are likely to remain the cheapest transport option for the foreseeable future, according to BloombergNEF analysis.

Source

BloombergNEF. Extracted from G20 Zero Carbon Policy Scoreboard report, published on February 1, 2021. Learn more about BloombergNEF solutions or find out how to become a BloombergNEF client.

Read next

Related actions

Support low-carbon hydrogen production close to demand

- Power and Grids

- Industry and Materials

- Companies

- Financials

Incentivize industrials to adopt zero-carbon processes and lower-carbon fuels

- Industry and Materials

- Financials

- Companies