Strategies to Incorporate Climate Risks and Opportunities into Decision-Making and Credit Assessment

Mandate companies and financial institutions to report their climate risks and impact, and integrate them into decision-making

Overview

Achieving net-zero emissions by mid-century in the real economy will also require a transition within the financial sector to more systematically account for climate change considerations in lending and investment decisions. But institutions striving to steer their portfolios into alignment with well-below 2-degree pathways face considerable challenges, beginning with significant data gaps in assessing climate risks and opportunities in their portfolio projects and companies. Where data is available, it can be difficult to integrate and standardize such information across risk management, strategy, and client engagement functions. Methodological approaches to portfolio alignment are under development. But these can be challenging to navigate and do not always resolve fundamental questions such as how to attribute emissions in financial portfolios. In addition, there are systemic challenges such as a focus on short-term financial incentives and a limited (but fast-growing) universe of low-carbon investment opportunities.

Despite these challenges, financial institutions are increasingly interested in exploring opportunities for climate alignment and a rich network of initiatives, methodologies, and frameworks are quickly emerging. While these initiatives lay the groundwork for significant progress in overcoming existing barriers to climate alignment, they are often applied to only one sector or kind of financial institution. To encourage a holistic approach that considers the integrated investment chain, financial institutions can collaborate to develop a consistent framework for climate alignment in support of the low-carbon transition.

Impact

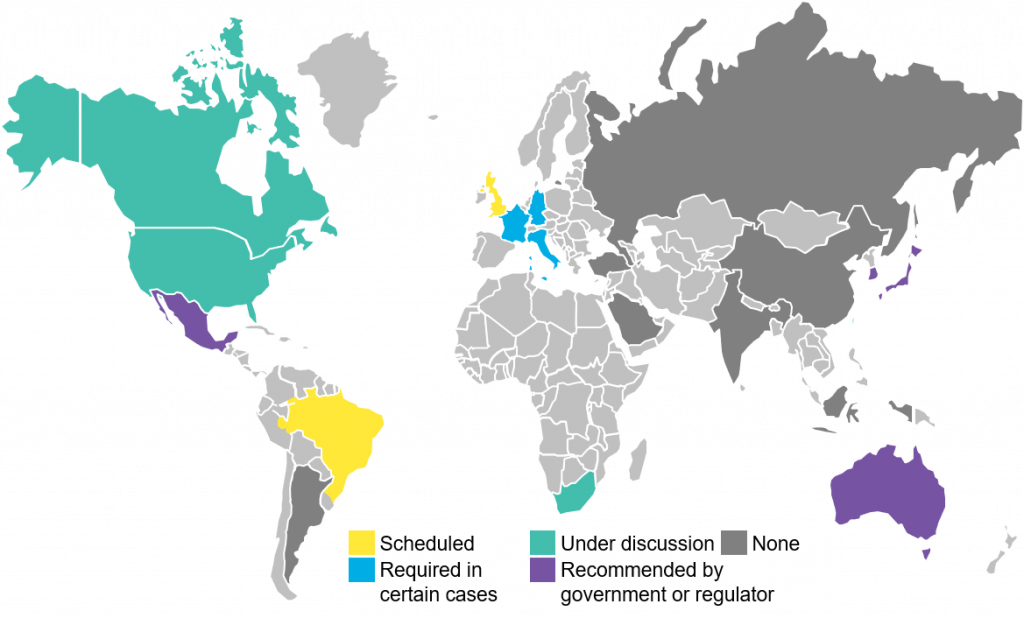

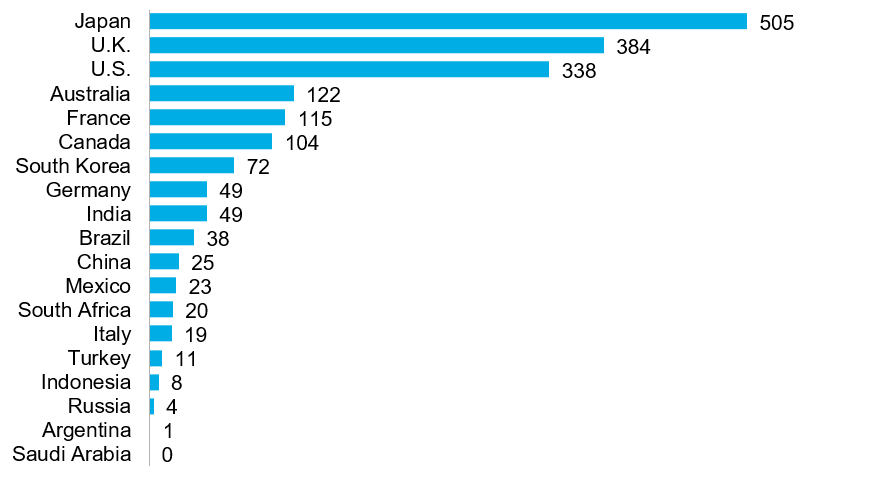

Private-sector institutions have often cited a lack of adequate decision-useful information on both climate alignment metrics and potential material climate-related information. Without widespread availability of such information, financial decision-makers cannot assess climate-related impacts for a single sector or asset class, let alone across an entire portfolio. In addition, climate-related reporting is not yet mainstream across all industries and regions. Only four of the G-20 countries – the U.K. and three EU member states – have implemented regulations to mandate climate-risk disclosure for investors. Even the most mainstream metrics, such as emissions, are not universally disclosed by corporations. The share of MSCI world index companies — collectively around 60% of world market capitalization — that disclose their emissions has stalled at around half in recent years.

However, several efforts to improve the availability and quality of climate-related information are under way, notably through the efforts of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The recommendations of the TCFD are increasingly recognized as the standard for effective voluntary disclosure of climate-related information and have broad support from financial institutions and across the private and public sectors. Investors need climate-related financial disclosures to evaluate a corporation’s commitment to managing climate risks and capitalizing on opportunities — and to allow them to factor those commitments into their portfolio management strategies. As of October, the TCFD had over 2,500 registered corporate, financial and government supporters. In addition, some countries and regions have implemented rules requiring disclosure in certain cases, such as the EU, while other nations such as the U.K. and Brazil have scheduled mandatory TCFD reporting for listed companies or banks.

* Source: BloombergNEF

* Source: BloombergNEF

Tools to help financial institutions measure and interpret disclosed physical and transition risks are still evolving and often lack standardization. The TCFD has also provided recommendations for conducting scenario analyses, which help organizations understand the potential impacts of climate change on their businesses, strategies, and financial performance, allowing them to better plan for and improve their resilience to climate risks.

Credit rating agencies play a role in encouraging the consideration of climate risks and opportunities throughout the financial system. The threats to supply chains, infrastructure, and organizations’ profitability from climate change are increasingly considered relevant to a borrower’s creditworthiness. For instance, following California’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire in 2018, sparked by electrical transmission lines owned and operated by Pacific Gas and Electric, Moody’s Investors Service downgraded the utility’s credit rating to Baa3 from Baa2 — the second-lowest level of investment grade. However, climate risks and opportunities are not yet fully or transparently integrated into mainstream credit rating methodologies.

Beyond the available quantity and quality of climate-related data, financial institutions face methodological barriers to aligning their portfolios with a below 2-degree trajectory – such as differing approaches to portfolio alignment and challenges to establishing emissions attribution. Appropriate alignment metrics are critical for steering reductions in portfolio emissions. Metrics commonly used for assessing alignment fall into two categories:

Assuming methodological challenges can be adequately addressed, the large-scale realignment of existing global investment portfolios with global temperature goals faces limitations on the supply of available low-carbon investments with which portfolios can be rebalanced. Most of the economy and, therefore, corporations, equities, and other asset classes are still largely misaligned with a well-below 2-degree trajectory, constraining the ability of financial institutions to transform their portfolios.

* Source: BloombergNEF

* Source: BloombergNEF

A fundamental challenge underlying the effort to align portfolios with temperature goals is the misalignment of time horizons whereby climate-related risks that could result in material financial impacts over the longer term are often not considered material today due to short time horizons for both regulators and financial market actors. In addition, while asset managers and asset owners are increasingly integrating climate-related factors into their investment decisions, these are often still considered separate and secondary to considerations of financial return.

Even if financial institutions overcome other challenges, portfolio alignment does not necessarily result in emissions reductions in the real economy. Assets sold by one investor can be purchased by another and simply held on a different balance sheet. Similarly, where commercial banks implement exclusions in their lending activities, carbon-intensive corporations and projects can often obtain financing from another bank (albeit at potential higher financing cost). From a global emissions reduction standpoint, it would be more effective for investors to identify and support relevant transition strategies while considering financial risk to help finance the transition of emissions-intensive industries.

Such assistance is often provided through soft engagement based on strong working relationships between financial institutions and the clients they serve. Asset managers and owners may also use shareholder votes to drive progress on climate issues and low-carbon transition strategies.

Opportunity

One key solution would be a framework for incorporating the low-carbon transition into strategy, capital allocation, and client engagement. Banks, asset managers, and asset owners can continue to incorporate consideration of climate-related risks and opportunities into governance, strategy, and financial decision-making. Financial institutions across the investment chain can also work to align financial portfolios with climate targets, including substantive efforts by lenders and investors to engage with corporations on climate-related objectives and transition strategies.

To facilitate material progress on both fronts, leading financial institutions can develop a harmonized framework for supporting the low-carbon transition through appropriately pricing risks and opportunities, providing guidance on alignment methodologies, and working with corporations to develop and support realistic industry-specific transition pathways. Finally, credit rating agencies can transparently integrate material climate-related information into their methodologies, allowing the private sector to steer capital accordingly.

Financial players can also set best practices for integrating climate factors into portfolio management. Public and multilateral financial institutions — notably development banks, sovereign wealth funds, and government pension funds — are themselves major investors. Their sovereign shareholders can lead by example by ensuring that these institutions move to align portfolios with well-below 2-degree pathways. MDBs and DFIs have charted a leadership path on Paris alignment, while SWFs and government pension funds can also integrate climate-related factors into their portfolio management activities. DFIs also can play an important role in helping to set minimum standards and in creating new asset classes in emerging markets.

In addition, central banks and financial regulators can continue to promote a better understanding of climate risks and potential financial implications. For example, they can assess the exposure of their domestic financial systems to climate-related risks, conduct climate stress-tests, and engage with financial institutions to ensure these risks are understood. They can also help encourage climate-related financial disclosure, for example, in alignment with TCFD recommendations. Policy makers can also develop standards and taxonomies to bring greater transparency about which activities are aligned with the low-carbon transition.

Greater emphasis could be placed on key levers for transition – eg, the construction of transition indices. Existing low-carbon indices are primarily composed of “deep green” investment opportunities, such as shares of renewable energy companies. However, by narrowly defining “green,” these indices neglect to account for corporations in high-carbon sectors that have adopted low-carbon strategies. Therefore, transition indices composed of these corporations — choosing those, for example, with the highest rates of improvement in their carbon intensity — would enable investors to more easily allocate capital to those preparing for the low-carbon economy.

Source

BloombergNEF. Extracted from DFLI report, published on September, 2019. Learn more about BloombergNEF solutions or find out how to become a BloombergNEF client.

Read next

Related actions

Mandate companies and financial institutions to report their climate risks and impact, and integrate them into decision-making

- Power and Grids

- Industry and Materials

- Transport

- Buildings

- Agriculture

- Financials

- Companies